I recently spent several days in a Kampala neighbourhood called the Acholi Quarter. This slum was formed over 20 years ago by northern Ugandans fleeing from the fighting between rebels and government forces that began in the 1980s. There were 11,000 people living here at last count, but that number has surely risen in recent years.

Grinding sesame seeds and peanuts (also known as “semsem” and “g-nut”). I truly enjoyed eating some local vegetables with g-nut paste!

During the conflict, the Lord’s Resistance Army under Joseph Kony kidnapped young girls and boys to serve the rebels as soldiers or slaves. Civilians were targeted, mostly from the northern Acholi ethnic group. Their crops were stolen to feed soldiers, and their homes burned.

Tens of thousands fled to the safety of Kampala, where they have now lived for up to 20 years. But the Acholi refugees that I met had only found a new sort of trouble. In the slum, whole families live in mud-walled homes with only a few rooms. There is little work except long days breaking rocks in the local stone quarry, a deep gash that runs through the Acholi Quarter.

Lots of children played by chasing tires up and down hills (at least when there were no foreign visitors to follow around!).

Many men, unable to find work or provide for their families, have turned to alcohol and domestic abuse. Women work selling vegetables on the street, or making bead jewelry. Many have lost respect for their husbands and their family relationships are not happy.

After rent, food, and medical costs, many parents don’t have enough many money for school fees for their children. Young girls turn to prostitution and boys drop out of school to work in the quarry. By night, I was told, the streets turn sinister and thugs roam.

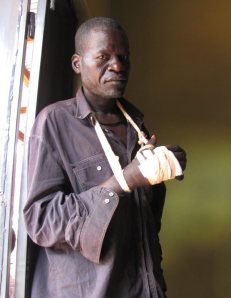

Jovino, who works in the rock quarry. When I first met him, his hand was grotesquely swollen from pounding stones with a hammer day after day. Someone at a tiny local clinic cut the infected area and drained his hand, and Jovino was regaining finger movement by the time I left.

Jovino’s wife making bead jewelry. The couple has 17 children in their household. Some are their own, others are orphaned relatives. Many families I met had taken in orphans.

Fighting stopped in 2008 when Kony and his army of indoctrinated child soldiers crossed into Congo DRC. With peace and stability returning to the north, the Acholi families here would love to return home. But they can’t, they all told me. It’s too expensive to move their whole families, rebuild their homes, and begin farming again. With their own land, they could grow their own food and escape the high costs and moral decay of their Kampala home, they said. But what would they eat for the first year, while waiting for crops to grow? Many were optimistic that they would return someday, but they could not say how.

For now, the newer arrivals rent homes from the refugees who arrive earlier and claimed a spot. There’s electricity, provided through dangerous-looking illegal hook-ups. A connection to the city water supply is possible, but too expensive, so families pay for each jerry can they need. It’s not a safe or nurturing place to raise a child.

Grinding peanuts into paste by hand. This woman sells chapati, eggs, and other goods by the roadside, and managed to save 75,000 shillings (around $30). She kindly lent that money to another woman, who is now refusing to repay.

I spent my time with Africa Arise , a group started just one year ago to offer personal and family counselling, as well as Christian discipleship. They hope to soon offer job skills training and, finally, resettlement opportunities for the stranded Acholi.

Conditions in the Acholi Quarter and the resulting social problems of substance abuse, violence and hopelessness, all resemble what I’ve seen in any slum or refugee community. Still, the people I met were extremely friendly, and warmly welcomed me into their homes. They seemed excited, even eager, to have a Canadian visitor, especially after I told them I would share their stories with my friends, family, and church back home.

I felt truly touched by their welcome, and by the difficult circumstances I saw. The past decades of violence have left lasting psychological scars. But the people in Africa Arise’s program said the counseling is making a real difference. “It’s released us completely,” one said. “It’s the only good thing here in the Acholi Quarter.”

Neighbours have taken notice of this new peace, and there’s a long waiting list to enroll in the next session. In a place that might look barren of hope, there seem to be some seeds still sprouting.