I’ve visited Kenyan schools before, but last week I met some special students. I spent a week at the PEFA Matumaini Centre (www.pefamatumaini.org) near the small town of Molo, which is home to 23 young people with physical and mental special needs. The centre also supports dozens more disabled children who still live at home or attend boarding schools. The centre works to demonstrate their motto, that “disability is not inability,” to both the children living in their dorms and to the surrounding community.

During my time here, I had the opportunity to befriend the staff and children. I helped serve a dinner of ugali and beans, and shared a Bible story with the children. We played kickball on the centre’s grass, and later started watching the classic 1980s movie “Karate Kid” (once the popcorn was devoured, most of the audience lost interest and left). A few of the high-functioning boys were always eager to use my camera and took hundreds of photos of themselves, their friends, and anything else they could aim a lens at.

As I got to know the children, I began to wonder just what made these kids “special needs.” For many, I could see why they needed extra care at the centre. Obvious medical problems like spina bifida, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy made eating, washing, or using the toilet impossible without help.

As I got to know the children, I began to wonder just what made these kids “special needs.” For many, I could see why they needed extra care at the centre. Obvious medical problems like spina bifida, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy made eating, washing, or using the toilet impossible without help.

But others seemed like fairly normal kids. They ran and played soccer, chopped wood for the kitchen, and didn’t strike me as particularly disabled. A club foot or a learning disability meant they had been classified as “special needs.”

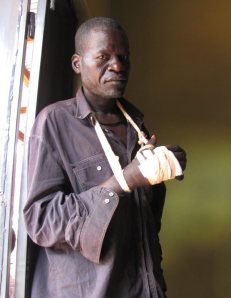

Harun squeezes water from a pulp made of sawdust and shredded paper. After drying, the charcoal is used for cooking fires.

Some local families, I got the impression, didn’t need much convincing to send their kids away to a centre that provided school sponsorship and food each day. It was a striking difference from how Canadian families react to special needs children, likely a result of different economic capabilities. But how did the children feel about being separated from parents and other kids to live in a compound with such a range of different needs? I never got the chance, or courage, to ask.

That’s not meant to diminish the PEFA Matumaini Centre’s fine work caring for children who have been diminished and marginalized. I really appreciated the centre’s focused motto of “empowering children to reach their God-given potential as responsible members of the community.”

Phyllis was often the slowest to get to church or meals, but always had a striking smile on her face.

The centre provides education sponsorship for kids to attend the area’s only primary school with a specific mandate to integrate special needs kids into regular classes. The school is next-door, just a few steps away from the dorms (still a difficult distance for some of the children). It’s much more basic than a Canadian special needs classroom.

Back at the centre, a volunteer physiotherapist works to strengthen and relax bodies tensed and twisted by years of seizures. The children learn to grow vegetables and wash their clothes, and to make charcoal from shredded paper.

Wyclef’s epileptic seizures have damaged his brain and his body. He can’t walk very well or eat by himself.

Living conditions for these kids aren’t necessarily bad, but they aren’t what I would want. As it does for many Kenyans, diet consists of mostly ugali and spinach or other greens. Beans are twice a week, meat is once, thanks to money from outside donors. Some children have no families able or willing to care for them, so they live at the centre full-time. Others live in the shared dorms just for the school year, then go home for holidays.

Many young people have been given staff positions after their school years finish. With more donor support, the director hopes to add new playground equipment and solar panels for power.

The young people seemed mostly happy, but some can also be obstinate and rude with staff. Have they been conditioned to be more needy or demanding by this childhood of special attention? What is the effect when a child is told they can’t learn or play like their friends?

John suffered a brain injury in an accident, but still loves music and sang for me several times. He always beckoned me to come sit with him, then spoke in a very slow, halting voice.

When does a child need special care, and when is it better to be left to adapt in the general population, as tough as that might be? My uneducated position is that applying a “disabled” label doesn’t help some children. I saw this at the centre, where children who limped with a club foot where lumped together with children with severe epilepsy and serious brain injuries. People had decided they were slow learners, but my impression was that the diagnosis may have been a bit fuzzy. Maybe they had a learning disability, maybe they could have thrived in a typical Kenyan class.

Catalina, a physiotherapist living at the centre, works with the children when they’re not in school.

I am certainly not qualified to make those important medical distinctions. But I did see a committed staff at the PEFA Matumaini Centre trying to improve skills, self-confidence, and ambitions for a large group of young people who otherwise may not have had many opportunities.