The “clink, clink” of hammer hitting rocks is the soundtrack of the Acholi Quarter. Like an unsteady metronome, it counts out hours and days here in the Kampala slum.

A rock quarry cuts through this hilly neighbourhood of tin-roofed wood and mud shacks. The steep canyon of brown stone and dirt runs alongside homes and streets where children play. It’s interrupted by a main city street leading to Kampala’s large Nelson Mandela football stadium, where the slum fades into urban development.

For most men in the Acholi Quarter, extracting stones and turning them into gravel for construction projects is the best work available.They break rocks with sledge hammers and steel wedges made from old car parts. Then, they carry the chunks to other workers sitting by the roadside who bash the rocks into gravel. They’re paid for each 20 litre plastic jerry can filled, with prices ranging from 200 to 300 shillings (eight to 12 cents) depending in the size of the crushed stones.

The first refugees who arrived here from northern Uganda, running from the atrocities of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army in the 1980s or 1990s, claimed an unofficial share of the quarry on a first-come, first-served basis. Division lines are marked on the rock walls with black steaks from burned rubber tires. Those owners now hire others to help bludgeon the earth into measly profits.

During my time in the Acholi Quarter, I spent a few hours with the men doing this job. For someone raised in a developed, industrial country, where so many jobs involve air conditioning, computer screens, and barely breaking a sweat, it was hard to comprehend that some people broke rocks all day to provide for their families.

My new friends, Churchill and Jovino, demonstrated their work for me. I was hoping for a fully hands-on experience, an expression of solidarity with the men who did this job for so many years. I did carry a rock chunk from quarry to roadside, then sat down for a few minutes to smash it into gravel. I managed not to crush my thumb, but my technique was poor and it would have taken me all day (at least) to fill one plastic bucket and earn my 10 cents. The experienced workers can fill a dozen jerry cans in a day.

My hosts didn’t let me get too dirty by working for long. I was also the target of some strange looks as passers-by observed this visitor with a hammer in hand. This is what workers here do in the hot Ugandan sun for nine hours a day, six days a week. If they’re less lucky, they are hired less regularly and can’t earn money each day to pay their rent and children’s school fees.

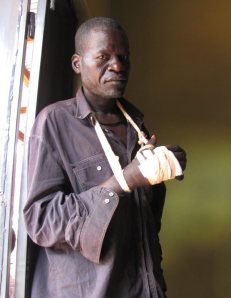

It’s not safe work. There are no hard hats, safety goggles, or fences around the quarry’s high edges. Churchill has a gapped smile after a chunk of rock flew into his face and knocked out a tooth. Jovino’s hand was grotesquely swollen and when I first met him, a somewhat common injury that results from the constant pounding of hammer on rock. It had to be drained and infected tissue removed. Another man’s foot was bloody and bandaged after stepping on a sharp shard. Men have died when an unstable rock wall collapses and crushes the workers at the bottom of the quarry. Even worse, playing children have run off the edge and fallen to their deaths.

Although the job is hard, the men I met wondered what they would do once the rocks were finally all gone. Each year, the quarry is dug deeper and available rock shrinks.

Seeing this work made me overwhelmingly grateful for the job opportunities back home. I can be confident that as an educated Canadian, I will never have to do such dangerous, boring, difficult work to survive. The industrial world’s job market and government supports make such a life nearly impossible. What a privileged and easy existence I have, completely unearned, simply because of my birthplace.

You can read my previous blog post about the Acholi Quarter by clicking here.